The Incoming Solvency Crisis That No One Is Pricing

When the next financial crisis hits, it may not begin on Wall Street or Threadneedle Street, and your balance sheet could be at immediate risk.

It will begin when the water reaches the electricity substation.

Flooding already causes more than US $100 billion in global losses each year, approximately US $10 million every hour,with an insurance protection gap of roughly 75% due to uninsured risks. The risk is not just physical. It’s temporal.

The Duration Mismatch

Mortgages last decades. Insurance renews every year.

That mismatch is the fault line, poised to slip.

When risk models shift, the first place it shows up is in the price and availability of insurance. That is precisely the kind of duration mismatch that triggered the Savings & Loan crisis of the 1980s, when banks borrowed short and lent long. When interest rates rose, their models broke, and so did their business.

Today, the risk is physical rather than monetary. But the mismatch is identical.

The financial plumbing that ensures everything works correctly depends on the assumption that the physical infrastructure will remain functional. But these pipes are corroding.

The Unpriced Mismatch

A quiet pillar of the economy is teetering: long-term debt built on short-term insurance.

Mortgages, commercial loans, and infrastructure bonds run for decades, but the insurance policies that secure them can be repriced or withdrawn annually. If flood premiums double or triple overnight, once-bankable assets may become uninsurable and therefore uninvestable.

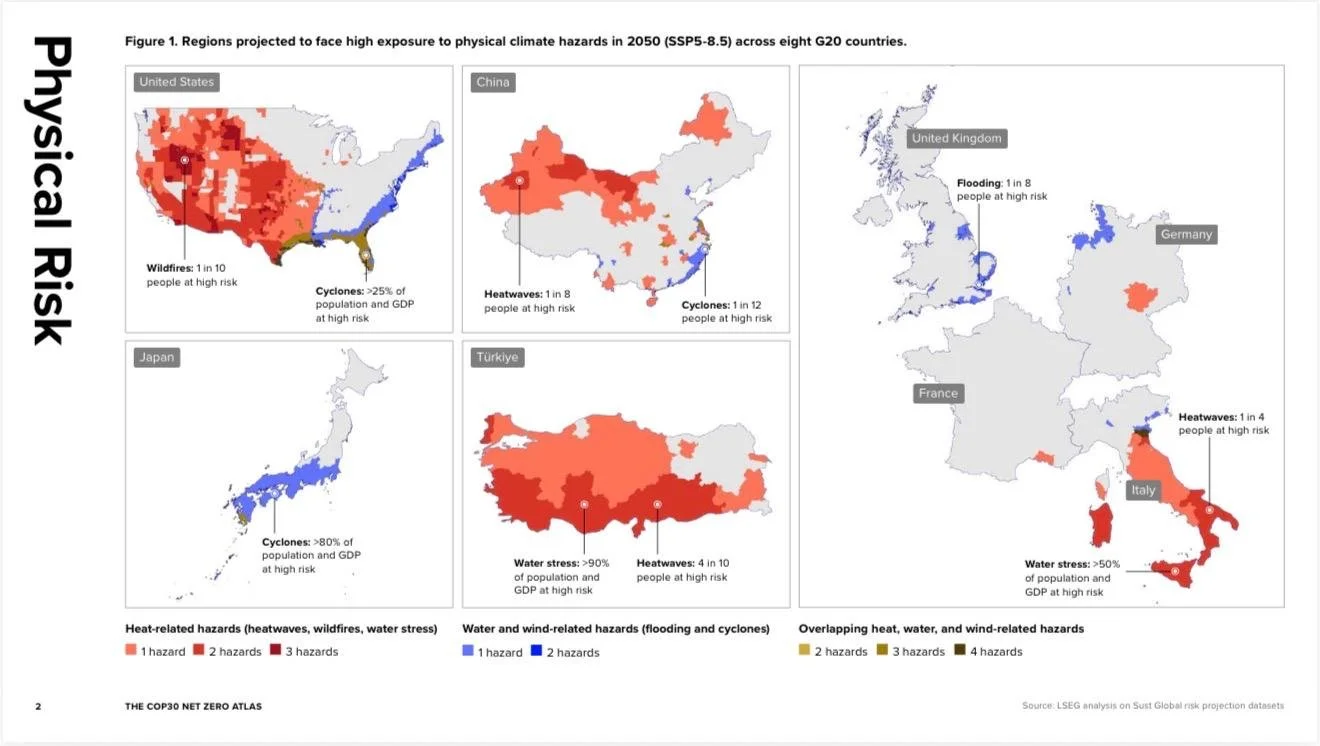

By 2050, almost 125 million people and US$4.5 trillion of GDP are expected to be located within high-flood-risk zones, more than doubling today’s exposure. Yet global markets still treat these assets as stable collateral, rather than at risk.

Consider a 25-year loan written today that will mature just as we reach 2050. The assets securing such a loan, once deemed sound, could face significant revaluation risk as these projections draw nearer, impacting not only the confidence of borrowers and lenders but also market stability. This link between long-term flood risk and short-term lending decisions highlights the need to integrate climate considerations into financial models now.

According to the CDP Water Directors Briefing 2024, water insecurity alone could place 7–9% of global GDP at risk,a figure “not fully priced into financial markets.” The same report warns of a 40% global freshwater shortfall by 2030. This is “an immediate, not a future problem.”

Every year, the losses climb: £573 million in UK home insurance claims from storms Babet, Ciarán, and Debi, and hundreds of billions worldwide for other climate-related events. But it’s the secondary effects that trigger contagion.

When the Floodwaters Hit

When the floodwaters rise, visible damage to cars, homes, and businesses is only the first indication of the shock. Then the infrastructure fails. Substations short out. Data centres go dark. Rail lines and logistics hubs are paralysed. Hospitals lose power, delaying emergency responses and putting patients at risk.

This cascade of failures shows why climate adaptation is a systemic imperative, not just an environmental one. When lifelines like roads, rail, and energy grids fail, the effects ripple through every sector.

Flooding isn’t just a natural disaster. It’s a balance-sheet event.

Motorway submerged as flash flooding hits the UK

America’s Warning Light

Across the United States, nearly 20 million people and US$2.4 trillion of GDP are projected to face high flood risk by 2050, rises of 160% and 300%, respectively.

Insurers are already retreating from entire states. As coverage disappears, mortgage lenders are left holding technically sound but financially stranded assets. The effect ripples through securitisation markets, resulting in higher collateral demands, tighter credit conditions, and reduced liquidity.

Every spreadsheet assumes the lights stay on.

When insurance fails, liquidity fails. When liquidity fails, solvency follows.

Britain’s Slow-Burning Exposure

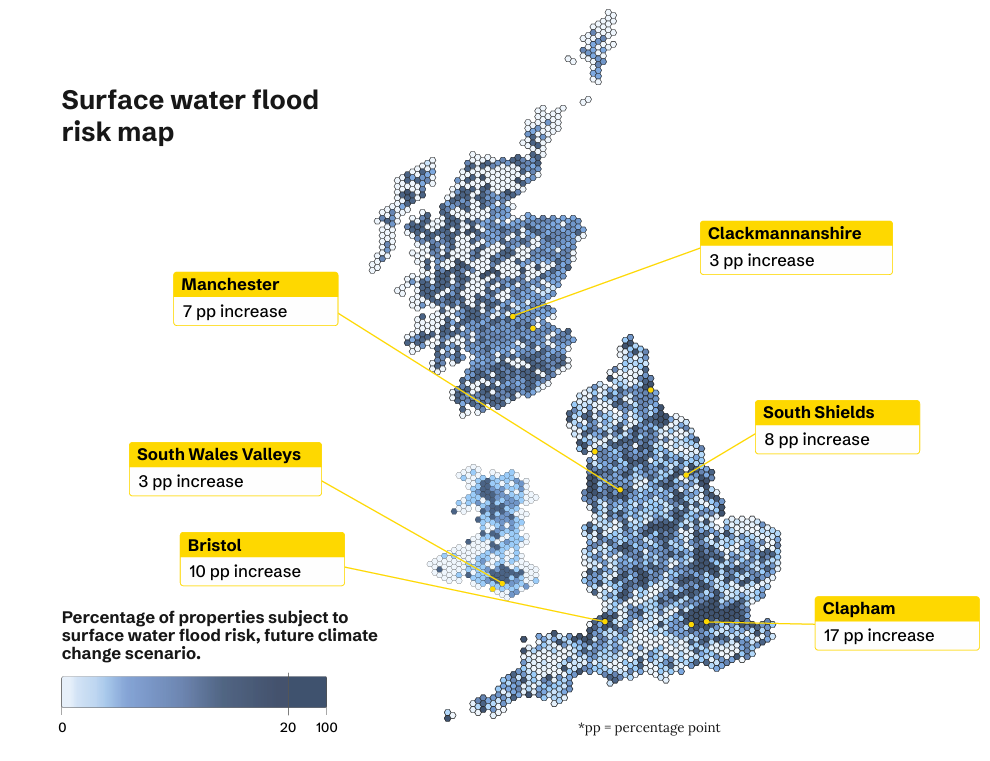

The LSEG Net Zero Atlas 2025 ranks Britain as the most flood-exposed economy in the G20. Around $100 billion of GDP and three million people are already at risk in the Thames Estuary. By 2050, that rises to 8.3 million people and almost 10% of national output.

COP30 Net Zero Atlas - Physical Climate Risk, LSEG 2025

Aviva’s 2025 Building Future Communities report shows:

One in four UK homes could face significant flood risk by mid-century.

83% of surface-water-exposed properties remain unprotected.

There is no equivalent mechanism for commercial property.

Projected flood risk and uninsured exposure by property type, Aviva 2025

The government’s Flood Re scheme, introduced in 2016 to keep household premiums affordable, is set to expire in 2039, with no successor planned.

That leaves industrial parks, logistics centres, and data hubs, the backbone of the modern economy, effectively uninsured. As coverage disappears, lenders mark down the value, borrowing costs rise, and refinancing becomes more difficult. The map of flood risk becomes the map of credit risk.

Yet examples like Trafford Park, Manchester, show what’s possible. A retrofit utilising natural water management solutions reduced flood exposure and increased investor confidence, providing a blueprint for how adaptation can protect both communities and capital.

The first casualties might be small businesses, priced out by premium recalculations. But like an avalanche, the impacts will be massive and far-reaching.

Insurance is the invisible thread connecting homeowners, lenders, and governments. When it snaps, the whole system unravels.

When Collateral Melts

The emerging insurance gap spreads through the system in three waves:

1. Mortgage stress (months): Uninsurable homes lose value and liquidity.

2. Commercial repricing (quarters): Exposed assets lose tenants and refinancing options.

3. Fiscal drag (years): As private insurers exit, governments inherit liability, stretching public finances.

CDP calculates that four stranded infrastructure projects have already cost investors US $13.5 billion. Yet 67% of financial institutions still fail to assess portfolio exposure to water risk.

The Network for Greening the Financial System, a coalition of 138 central banks, warns that “nature-related risks are not yet priced into financial markets,” leaving capital flows “misaligned with societal goals.”

We are still lending to homes on floodplains and building data centres in water-scarce drainage basins. That’s not resilience. That’s a huge blindspot on long-term debt.

The Price of Inaction

Under English law, directors who fail to consider foreseeable environmental risks can face liability for breach of duty. Managing adaptation risk is therefore a fiduciary responsibility.

If assets are stranded by water rather than carbon, the outcome is the same: falling values, frozen credit, and government bailouts. Adaptation failure directly impacts financial stability, pension security, and a country's sovereign credit rating. It is a balance-sheet issue, not an external factor.

How to Avert a Climate-Driven Solvency Crisis

Silent, compounding mismatches and untenable assumptions can trigger crises. To prevent a climate-driven solvency crisis, financial and physical resilience must be linked from the outset.

Before we sleepwalk into an economy-melting Black Swan event, directors must recognise that climate adaptation is a duty of care, not an ESG aspiration. The question is no longer whether to act, but how swiftly.

Integrate adaptation into infrastructure investment.

Natural systems, such as wetlands, peatlands, and oyster reefs, can store water and dissipate floods far more cost-effectively than concrete. Pilot oyster-reef restorations have shown up to a 70% reduction in flood-prevention costs compared to traditional barriers.

Reinvent insurance

Shift from annual renewals to multi-year, performance-linked cover. Reward resilience, not exposure. If a property stays resilient, premiums should fall.

Make physical risk visible in valuation

Integrate climate-risk metrics into credit ratings and regulatory stress tests. Frameworks like TCFD and ISSB already exist to connect market valuation with physical risk.

Blend public and private capital.

A Resilience Re Fund could extend the Flood Re model beyond homes, co-insuring critical infrastructure with institutional capital. By pooling risk between the government, insurers, and investors, such a vehicle could keep premiums affordable while funding large-scale adaptation.

When natural systems fail, the cost doesn’t disappear; it migrates.

Households --> high bills

Employers --> lost output

Sponsors --> delayed projects

Pension savers --> weaker returns

But when natural infrastructure functions, it protects the very assets and communities our economy relies on.

This is no longer an environmental issue.

It’s an economic one.

But what if cities went further?

Imagine Manchester launching a cooperative insurance scheme backed by both the public sector and private capital, which rewards climate resilience with lower premiums. If homes, industrial estates, and data hubs were retrofitted for flood resilience, those savings could be shared between policyholders, the city, and investors. Over time, the city’s resilience would become its credit strength. Such an approach could:

Turn resilience into a financial advantage for cities, not just a cost.

Incentivise citizens and businesses to adapt through measurable savings.

Create place-based insurance pools that attract institutional capital seeking stable, long-term returns linked to avoided loss.

This model combines public accountability with private discipline, utilising financial innovation to mitigate systemic risk rather than exacerbate it. In doing so, cities like Manchester could lead a new wave of climate-resilient municipal finance, where adaptation is rewarded, premiums fall, and solvency strengthens at every level from household to balance sheet.

But within every crisis lies an equation, and this one can balance in our favour. Because the same forces that threaten solvency can also generate new, investible forms of stability. If we can price resilience, we can fund it. And if we can fund it, we can compound it.

Resilience as Return

If we align resilience with returns, adaptation becomes an asset class.

Resilient infrastructure isn’t a sunk cost; it’s an investment in continuity, credit quality, and cash flow stability. Projects that reduce flood, drought, or heat exposure deliver measurable risk-adjusted returns, lowering insurance costs, protecting asset values, and preventing operational disruption.

Across the UK and Europe, nature-based solutions are already generating IRRs above 10% comparable to traditional infrastructure, but with lower correlation to markets and higher social value. Wetlands, oyster reefs, and reforested catchments reduce insurance losses, extend the lifespan of assets, and strengthen local economies. Their benefits are physical first, but their financial payback compounds with every avoided loss.

When you invest in resilience, you’re not speculating, you’re stabilising. The return comes from protection as performance: fewer claims, fewer shutdowns, fewer write-downs.

If scaled across portfolios and regions, the cumulative value is enormous. A shift from reactive repair to proactive adaptation could unlock enduring savings and generate recurring revenues from avoided costs, ecosystem service payments, and performance-linked insurance models.

Nature-based resilience doesn’t just pay. It compounds financially, ecologically, and socially.

Natural systems are critical infrastructure:

They slow water.

Store water

Filter water.

Protect assets.

Reduce risk.

Stabilise cashflow.

This isn’t CSR.

It’s economic stabilisation.

It’s a fiduciary duty.

It’s national competitiveness.

Closing Thought

The last crisis was about interest rates. The next will be about rainfall rates.

Markets will eventually price physics; the only question is when. Because solvency isn’t just about capital. It’s about water, too much, too little, too dirty.

Resilience isn’t a cost. It’s collateral.